Canadian independent publishers rebuild after Meta ban

Banned from Facebook and Instagram in 2023, Canadian independent news outlets have developed formats and forged collaborations to bounce back. While this crisis has been a significant blow, it has also pushed the media to question their relationship with tech platforms.

Cet article a initialement été publié en français.

English speakers, find out more about Médianes on our About us page.

“Will they really dare?” wondered Canadian newsrooms - and their international counterparts - in the summer of 2023. For the past few weeks, Meta has been threatening to cut off access to the Canadian press in response to the Online News Act, a law passed by the Senate in June 2023, which requires large tech companies, including Meta and Google, to pay publishers for the distribution of its content.

An affront, according to Meta, which prefers to pour billions of dollars into the virtual realms of the metaverse and draw on libraries of pirated books to train its AIs rather than strengthen journalism. A curious turnaround for a company that until recently claimed that journalism played an “important role in seeking out the truth, telling the stories that define Canadians and holding powerful people and institutions accountable” in a post praising Meta's role in the media ecosystem. In the same note, a short passage now takes on a whole new meaning: “links make up less than 3% of what Canadians see in Feed.” What appeared at the time to be an innocuous statistic is now revealed to be a thinly veiled warning: “You need us much more than we need you.”

“We thought they must be bluffing, as if a mega tech company would question the ethics of banning the press from its platforms,” recalls with bitter hindsight Savannah Stewart, managing editor at The Rover, a reader-funded investigative outlet from Montreal. But in August, Mark Zuckerberg's firm took the plunge: Canadian publishers were officially banned. On Instagram and Facebook, their accounts became inaccessible, replaced by a terse message: “In response to Canadian government legislation, news content can't be viewed in Canada”. Translation: Meta had no other recourse, despite Google signing a deal a few months later agreeing to pay $100 million to Canadian outlets.

Meta's decision dealt a severe blow to the Canadian media ecosystem, drastically affecting audiences and undermining the financial stability of many publications. However, teams quickly explored alternative avenues and developed new strategies to bounce back and win back their audience.

Keeping in touch with the community

When Savannah Stewart joined The Rover in May 2023 as managing editor, she set herself a goal: to develop their presence on Instagram. “I really wanted to relaunch the Instagram account. We went from 1,000 subscribers to 3,000 in the space of a month and I was happy.” But in August, the axe fell and the team lost access to this segment of its community.

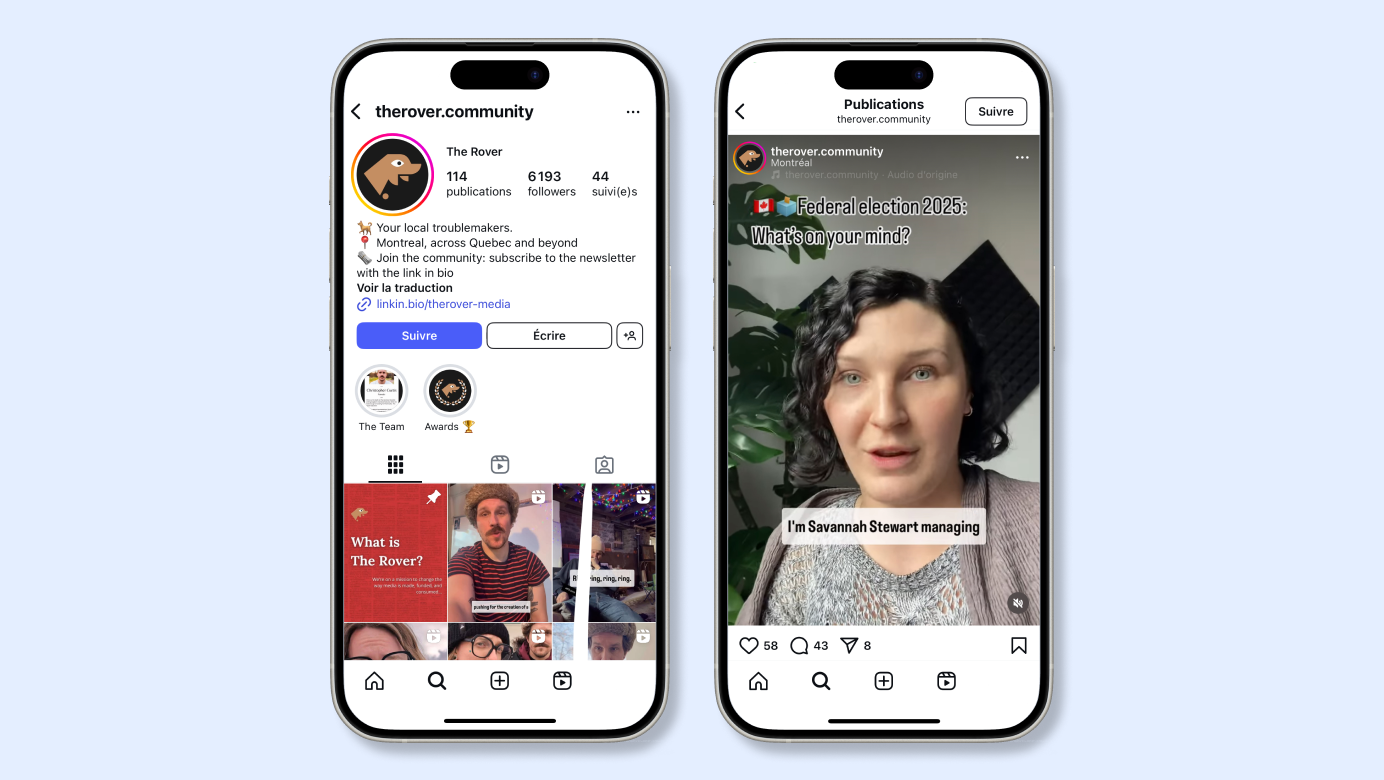

For The Rover, with 80% of its budget coming from readers, maintaining contact with its community is vital and the team decided to try a new strategy. Rather than giving up on Instagram completely, it transformed its use and created a new account, therover.community, where the team now publishes videos with journalists taking the center stage, in a vlog-style format, in order to share behind the scenes, thoughts on journalistic practices, cultural suggestions, etc. The tone is more embodied, designed to encourage dialogue, and the journalists only refer very briefly to the news, to avoid triggering Meta's algorithms. The team uses this space to interact with its readers by inviting them to ask questions and respond to their comments. This practice, also adopted by other newsrooms in Canada to circumvent Meta's new rules, is working. Today, this new account has more than 6,000 followers, compared to 3,000 on the old one. “We are regaining our momentum,” says Savannah Stewart. A strategy focused above all on behind-the-scenes information that is reflected in the media's overall editorial approach, notably through a new format launched this past January: “Editor's Note”, a monthly column written by Savannah Stewart that aims to to reveal what goes on behind the scenes through various topics : finances, editorial reflections, etc. The Rover can also count on its newsletter (6,500 subscribers), which, like many other newsrooms, has been a valuable channel in this time of crisis.

This was the case, for example, for The Tyee, a media outlet based in British Columbia. Launched in 2003, a few months before Mark Zuckerberg launched his project from his student room at Harvard, the local outlet did without social networks for a while. However, like the majority of its peers, The Tyee ended up integrating Meta's platforms into its communication arsenal. At the time, the American firm stepped up its efforts to please publishers and present itself as a solution to their problems. An investment from which The Tyee even benefited, receiving a grant from Facebook in 2019. Ironically, it was a program to help the media retain their audiences.

David Beers, founder and editor-in-chief of The Tyee, was not fooled: “Facebook was mainly trying to defend itself against the regulations and government interventions it is facing today all over the world. It was trying to fend them off by co-opting the media and befriending them in different countries”.

The Tyee quickly became wary of the use of Facebook, warning of the sector's growing dependence on the platform, particularly in the late 2010s when its approach to topics such as disinformation raised doubts and concerns. So when the ban came into effect in 2023, The Tyee was able to draw on a valuable - and substantial - database of email addresses that it had patiently built up over more than twenty years: “We would set up stalls at folk festivals and sign people up one by one to receive the newsletters,” he recalls amusedly. Today, this database gives the organization direct access to its readers, without depending on platforms. It also allows it to convert readers into donors more precisely and effectively: “You don't have total control over Facebook and other platforms, but you do have a lot of control over email because you can segment your lists and talk directly to specific members,” argues the head of The Tyee, which currently offers six different newsletters.

Joining forces

In response to Meta's decision, several independent Canadian outlets have also come together around a common project: Unrigged, a site that aggregates articles, podcasts and newsletters from partner newsrooms in a mainly chronological feed, unaffected by algorithms. André Goulet, podcasts producer and host, had already been considering the project in the run-up to summer 2023, but the decision by Meta greatly accelerated it: “We worked flat out to create the website and bring all the collaborators together. All this was done in about five months, between June and November 2023,” remembers André Goulet, who previously launched a similar project dedicated to podcasts and now co-organizes Unrigged as community director. « The relationships behind the scenes are such that it's never really top-down » he adds. « The decisions are made collectively, for instance, when it comes to bringing on new publishers ».

Supported by grants and accompanied by SEIZE, the solidarity economy incubator of Concordia University, the platform does not require any financial participation from its members. In exchange, participating outlets only agree to promote the platform to their readers. Eighteen months later, André Goulet claims success in terms of traffic. But beyond theses metrics, the platform has created the ideal conditions to encourage newsrooms to get closer, even to the point of sharing resources. “I'm in the offices of La Converse right now and that kind of happened as a result of Unrigged”, Savannah Stewart explains behind her webcam, adding that their mutual participation in this project has brought the two Quebec newsrooms closer together. The crisis caused by Meta has encouraged sharing and collective dynamics between newsrooms she explains: “Despite the blow we took when we lost access to Facebook and Instagram, I think it gave us a reason to put aside our petty differences or competitiveness to see what we could do better if we worked together. I do think the independent media scene is a lot stronger because of a project like Unrigged.”

An opinion shared by André Goulet: “Since our launch, the process of building a space where people can bypass the competitive factor - even if it is always part of the equation - to build relationships and find ways to stimulate each other, to collaborate and to amplify each other, has proven to be interesting.”

For David Beers, collaboration can also involve sharing audiences. A strategy that has already been adopted by The Tyee, which suggests a curated list of articles from other publications on its website and republishes stories from other publishers, such as The Conversation, whose articles are distributed under a free license.

For David Beers, this need for publishers to bring communities together could result in the emergence of a new generation of press groups: “We may see a renaissance of media conglomerates. You could create your own title alongside another and, because you are part of the same company, you would be helped in finding subscribers by advertising your newsletter in others.”

One step forward, one step back?

While traffic initially decreased in the aftermath of Meta's decision for The Tyee, it has now never been higher. The editor-in-chief partly attributes this phenomenon to a proactive approach by Canadian readers in their consumption of information, who are now seeking to forge concrete and solid links with their outlets, or even to finance them, knowing that they will no longer have access to them via Facebook or Instagram. “We are seeing a sharp increase in the number of people who come to the Tyee on their own,” he observes. This dynamic is part of a tense political context, fueled by Donald Trump's antics against Canada, which has rekindled interest in information that is rich and comprehensive rather than simplistic and digestible. This trend is particularly noticeable among the younger generations, who now look to publishers for human interactions and information to build concrete solutions. For David Beers, “it is not enough to say that, by the standards of good journalism, we are doing good journalism”. To stand out and make themselves indispensable to their readers, he believes that newsrooms must focus on their local roots and their values: “If I'm a progressive person living in British Columbia who needs to know what is going on in my work and my life, I cannot imagine The Tyee disappearing”. A clear interest from certain groups of readers for news that shares their own point of view, rather than so-called « impartial news », which has been documented in a recent studies.

For Savannah Stewart, this crisis has mainly pushed publishers, including The Rover, to re-examine their relationship with platforms in general and to strengthen their digital sovereignty through projects such as Unrigged and native formats: “We realized that we didn't own our Instagram account. It can be taken away from us at any time. I think there has been a kind of realization: we need to focus on what we own". Despite this progress, the ban is both a blow and a cause for concern. Facebook is still a major information tool in some areas. “What will happen to small independent publications, those serving northern and indigenous communities? asks Savannah Stewart. Social media is a big part of the business model of these small newsrooms.” For Eden Fineday, editor of IndigiNews, an online news outlet based in British Colombia, the situation is “even more catastrophic” for indigenous outlets, she said to Radio-Canada. For the online publisher, strengthening its efforts on its newsletter is therefore not enough. IndigiNews, which derived 40% of its total traffic from Facebook, has tested various strategies, including displaying QR codes in public spaces that redirect to their content. Like many other newsrooms in Canada, IndigiNews has also used Facebook ads. Ironically, if Meta blocks the press because it does not want to pay for it, it is still possible for newsrooms to pay the company for sponsored content that redirects to their articles. Eden Fineday did the math for CJR: paying to post each article on Facebook represents an annual budget of between $15,000 and $20,000. Faced with opaque moderation rules and algorithms, Canadian newsrooms are navigating by sight and testing the limits of Meta. To avoid being censored, Unrigged is careful about the vocabulary it uses: “Facebook has not yet banned Unrigged. We just avoid saying the word “journalism” too often in our publications,” explains André Goulet.

An uncertain future

But if newsrooms like The Rover or The Tyee manage to limit the damage, it can largely be attributed to the fact they already had a pre-existing community and a solid local foothold. While newsletters, for example, seem to offer an interesting solution, they do have a major limitation. While social networks can act as a kind of large showcase - albeit a flawed one - through which a reader can stumble upon a news article, somewhat by chance, it remains much more difficult to unearth new newsletters and websites without a major relay. Meta's decision could thus pose a much greater threat to newsrooms that have not yet been established and curb the emergence of new independent journalism. “We will get through this, we may become smaller, but we will continue to exist,” says David Beers. But what Facebook is doing is sterilizing the soil. No more seeds will grow.”

Opinions differ on the benefits of this law. Even the sum paid by Google ($100 million) is well below official forecasts, which were based on a contribution of $172 million. Today, those suffering the drastic consequences of the Online News Act are publishers, and not only small ones, who are painstakingly picking up the pieces. Meta, for its part, prefers to run out the clock, even if it means allowing misinformation to spread. The law provides that its results will be reassessed five years after its implementation, i.e. in 2028.

To go further

- Faced with the rising cost of paper and growing dependence on social media algorithms, URBANIA has chosen to regain control over its distribution. Learn more about the Micromag, a 100% digital magazine hosted on their website.

- Unpredictable algorithms, collapsing traffic, dependence on platforms: publishers find themselves trapped by an Internet they no longer control. How can they maintain a connection with their audience? Discover an overview of current initiatives.

- Where democratic freedoms are threatened by the rise of the far right and where media concentration weakens the diversity of information, pooling ressources and teaming up becomes essential for independent media.

La newsletter de Médianes

La newsletter de Médianes est dédiée au partage de notre veille, et à l’analyse des dernières tendances dans les médias. Elle est envoyée un jeudi sur deux à 7h00.